Nicoló Paganini

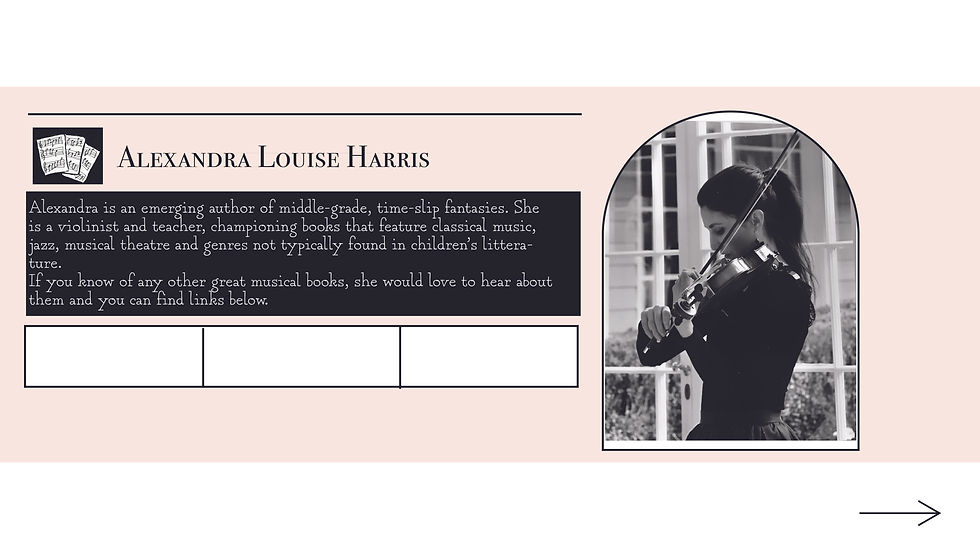

- Alexandra Louise Harris

- Aug 8, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Feb 3

Excerpts from Mighty Muso - Musings behind Violetta's adventures for adult minds and readers.

Some people seem to walk on stage full of confidence, every time. Nicoló Paganini (1782-1840) was one of those superhuman individuals. In fact, he was so good, many believed he was possessed. Like Faust, people believed he made a pact with the devil. He acquired magical powers and was gifted the ‘musical diablerie,’ with tricks like left-hand pizzicato, up-bow staccato; and, of course, playing an entire piece on a G string.

I know. That always gets a laugh, particularly with teenagers, but actually, Paganini was quite a fan. Of the sound, not the underpants. After being challenged at a party to play upon one string, he said: ‘This is the genuine and original cause of my prejudice in favour for the G string. People were afterwards importunate to hear more of this performance, and in this way I became day by day a greater adept at it, and acquired constantly increasing confidence in this peculiar mystery of handling the bow.’

He was so enamoured, he even wrote a sonata on the G string for Napoleon’s birthday.

Johan Wolfgang von Goete (1749-1832) popularised Faust, the character of German legend,. His pact with the devil brought knowledge and possessions. In Paganini’s time, there was a bit of a craze. Weber wrote a Faust violin sonata (1811), Berlioz wrote 'La Damnation de Faust' (1846), and there was the novel Le Faust by Christopher Marlowe (1858) and he gets a mention in Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Grey (1891). Dorian gives up his soul for eternal beauty. One can understand the appeal, and the Faustian trend was quite tremendous. I’m sure they had t-shirts; and explains why Paganini’s contemporaries leapt to the conclusion that the ‘wizard’ Paganini surrendered his soul to become a fiddler extraordinaire.

‘Let us rejoice that this enchanter is our contemporary,’ was written after one of his performances, and ‘let him be glad of it himself; if he had played his violin like that two hundred years ago, he would have been burned as a magician’ . When audiences witnessed Paganini ‘waving his bow in the air, he appeared more than ever like a wizard commanding the elements,’ some described his bow as a broomstick. He was called names in the local papers—not very nice ones—but most of the comparisons were devils or witches. Perhaps that’s why he wrote his 'Le Streghe' or 'Witch’s Dance'? After all, if people insist on comparing you to a sorcerer, you might as well write a tune to witch they tap their feet.

See what I did there—witch and which? I know, it’s almost as bad as a dad joke…

Moving on; in the famous illustration by Johan Peter Lyser in 1782, titled Paganini der Hexenmeister, the poet Henrick Heine (1797-1856) believed: ‘that only one man has succeeded in putting Paganini’s true physiognomy upon paper—a deaf painter, Lyser by name, who in a frenzy full of genius has with a few strokes of chalk so well hit the great violinist’s head that one is at the same time amused and terrified at the truth of the drawing. ‘The devil guided my hand,’ the deaf painter said to me, chuckling mysteriously, and nodding his head with a good-natured irony in the way he generally accompanied his genial witticisms.’

The Hexenmeister in the illustration is surrounded by superstitious objects. A black cat, human bones and skeletons, a snake, a sword and a star of David. However, in order to become the devil, a person needs to be dead... and people thought he was! Hein wrote; Paganini was ‘a corpse risen from the grave, a vampire with a violin’ with his ‘cadaverous face’. He was pale, tall, wore a lot of black, and had unfortunate afflictions like an abscess on his chin from playing.

Unfortunately, Paganini’s health was poor most of his life. He had the measles as a child, and was almost given up for dead. Fortunately, he started playing the violin. His father encouraged him and Paganini practised excessively, despite being a ‘sickly child’ (Dubourg). At seventeen, however, he rebelled. He escaped his strict father and plunged into ‘severe bohemianism... and a fatal passion for gambling,’ even losing his violin. Luckily, someone gave him another—a Stradivari, no less.

Writing about the lives of such composers for children means treading lightly around certain details. But does that mean we shouldn't mention them? For most of his life, comparably short by today’s standards, Paganini had a pretty terrible reputation. The papers were scathing, and he was imprisoned, suspected of murder, with only his violin for company. Was he guilty? No, but things only got worse. When Paganini moved to Paris, he wanted to open a casino. I agree. It sounds like a terrible idea for someone of Paganini’s inclinations, but he had reformed his ways. He’d turned a new leaf, given up his gambling past, and when he proposed the plans of his casino, the Parisian government had enacted a ban on all gambling.

Unfortunately, historical information can be rather unreliable. The record states that Paganini was refused a gambling licence. It suggests gambling was his primary motivation in opening such a venue, escaping the notion that the word ‘casino’ in the Italian language refers to ‘casa’ meaning house... or making a mess. A messy house? Paganini had great intentions for the place; decorating it like the Palace of Versailles with concert halls, a library and a ballroom.

Paganini’s vision, to my mind, seemed ahead of his time. Perhaps it would have been better received during the magical belle époque? The original plans had the building standing in the more bourgeois area of Paris rather than the bohemian Montmartre, but the spirit seems consistent. A place for art to flourish, where music could be enjoyed by all. His enjoyment of the Parisian bohemian lifestyle also made me wonder if Paganini himself belonged to a different era. Maybe he would have felt more at home in Paris during the Belle époque? It sounds as though his time in Paris was pretty awful. Of course, I didn’t know Debussy, Satie or the young Ravel personally, but from what I have read, they would have welcomed him into their society of musicians with open arms.

That’s what I like to believe, anyway. It also inspired the emergence of the Academie du Paganini. A fictional establishment where Hogwarts meets the Adams family in 1890, Paris. Yep. Totally bizarre, and if you’re intrigued, more oddness can be found in Violetta and the Paganini Poltergeist.

Mostly, however, I wondered… was Paganini misrepresented in history? People—even people who don’t always make excellent decisions—are not all bad. Humans are multifaceted, capable of change and many miraculous things, and like celebrities of our society; you can’t always believe what you read. He was an incredible violinist and a musician with a legacy inspiring musicians generations later, and many more to come. Can we really believe all we read?

Steven Samuel Stratton (1907) observes, ‘There is nothing malicious in these stories of the devil and the fiddler; and if Paganini had experienced nothing worse than what had just been related, he might have treated the matter as a joke. But that which malice or envy originated, a “reptile press” promulgated. Innocent of crime, Paganini was branded as a felon; gifted with genius of the rarest order, cultivated to a perfection absolutely unique, his skill was attributed to the aid received from the devil. Add to this his wretched health, and there is both mental and bodily suffering. In his later years, he was cut off from intercourse with others, like Beethoven—but with this difference: Beethoven employed a tablet or notebook for his friends to convey their words to him; Paganini transmitted, through a similar medium, his thoughts to others. He was dumb!’

Yes, he lost his voice. In the memoirs of Héctor Berlioz (1803-1869) he mentions meeting with Paganini: ‘Due to this laryngeal disorder, he had completely lost his voice and only his son … could hear, or rather guess, his words.’ As a result, when he died, he was unable to make a confession, therefore, at first, they refused to bury him on consecrated ground.

Malice and envy, prejudice and misunderstanding could have been a larger part of Paganini’s life than we realise. It also highlights an important point in relation to talent. Unfortunately, with ‘tall poppies’ like the long and lean and clever Paganini, sadly some people relish chopping them down.

Luckily, us mighty musos aren't among them.

‘Let us rejoice…’Castil-Blaze in Journal des debate (March, 15, 1831) ‘let him be glad…’(quoted in Metzer 1998:131) ‘waving his bow’ (quoted in Heine 1933:48). Sourced in Kawabata, M. (2007). Virtuosity, the violin, the devil…what really made Paganini “demonic”? Current Musicology, 83.

‘This is the genuine…’ Paganini’s account to Professor Julius Schottky in 1805, cited in Stratton, S.S (1907) Nicoló Paganini:His life and work. Shore and co. London, sourced through Project Gutenberg.

Heine Hamburg (1829), sourced in Stratton (1907).

(Hein 1933:38,42) sourced in Kawabata (2007).

Berlioz (1870) Mémoires de Hector Berlioz meeting with Paganini in 1838 cited in Sperati, G., & Felisati, D. (2005).

De Sousa, E. (2013). THE IDEA OF VIRTUOSITY IN KIERKEGAARD'S THOUGHT. Rivista Di Filosofia Neo-Scolastica, 105(3/4), 987-1000. Retrieved August 22, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/43064121

Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, N. (2001). Blemished Physiologies: Delacroix, Paganini, and the Cholera Epidemic of 1832. The Art Bulletin, 83(4), 686-710. doi:10.2307/3177228

Sperati, G., & Felisati, D. (2005). Nicolò Paganini (1782-1840). Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale, 25(2), 125–128. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2639882/.

Comments