Scriabin and space

- Alexandra Louise Harris

- Feb 16, 2022

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 8, 2024

Excerpts from Mighty Muso - Musings behind Violetta's adventures for adult minds and readers.

Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) thought about transcending too; but before I explain, I must tell you of a fun-filled fortnight spent analysing a Scriabin piano sonata for a harmony project at University. I remember it vividly. The oak floors of our college library, the sun streaming through the french windows, the bookshelves filled with old volumes, and the wafts of various casseroles and overcooked broccoli emanating from the kitchen. It was very inspiring.

Anyway, I was good friends with a guy from University during that time. He was clever, loads of fun and when he accompanied me to my college ball, he even made me an awesome mask (If you know anything about my Violetta books, you know I love these). Anyway, for a brief time, we were obsessed with Scriabin. Hilarious really, as we spent hours and hours on this particular assignment but in the end, we both got the highest marks we had ever received in Harmony and Analysis—ninety-seven percent. You see, we cracked the code.

I really wish I could remember which particular sonata it was, but somehow, it all came down to the number four. Every note, and every interval could fit into a divisible equation, and it was very satisfying!

In fact, Scriabin was known for his love of fourths. He built a chord based around them and called it… “the mystic chord”. He was obviously a man after my own heart. I love the number four too, and throughout history it has been associated with all kinds of things. Of course, there are the four seasons, beautiful in Vivaldi’s music and nature too. Then according to Mirapuda—the talking dog in Violetta and the Venetian Violin—there are also four violin strings, four planets, the four groups of gods, t

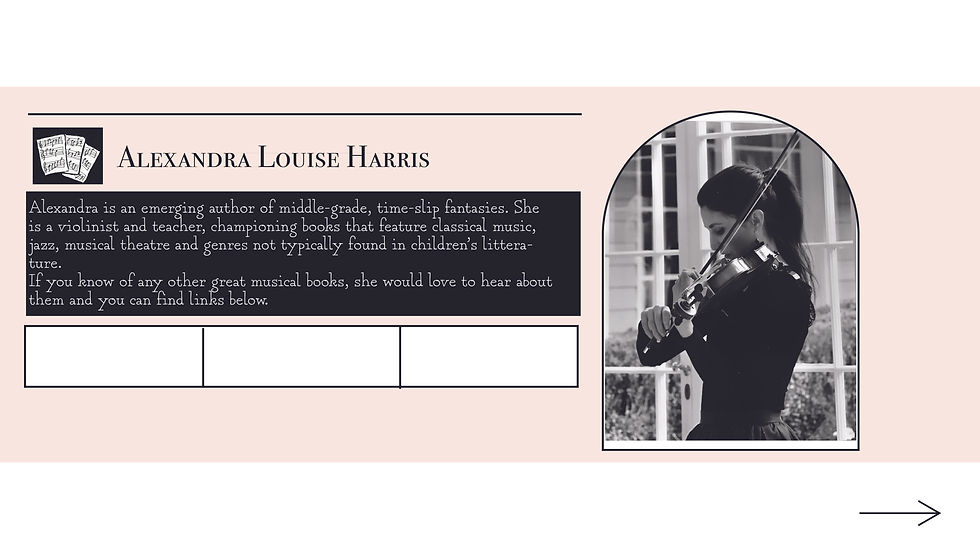

he four horses of the apocalypse. The four humours; phlegm, blood, choler, and black bile—’ (The above is an image from Violetta and the Venetian Violin featuring the four violins and violinists.)

Mirapuda was slightly misguided about the number of planets, but if you remember, we talked about the tetractys earlier, and the universal harmony in which the sirens sing. This is most often known as the common chord formation; I,IV,V,I, used in nursery rhymes like Hey Diddle Diddle, and Mozart’s famous ditty—Twinkle Twinkle. It is also used in much popular and folk music like A Thousand Years, and The Yellow Rose of Texas, and the formation has become part of our musical DNA.

Scriabin also did some other groundbreaking things. He was interested in colour and music and as a synesthete himself, he saw a direct link and used a coloured organ to show this in Prometheus:Poem of Fire.

However, later in life, in 1903 when he started writing Mysterium, he had the end of the world in mind—in an apocalyptic sense. This is where Scriabin and space come together. The work almost possessed him until his death, and although it remained unfinished, it was a mammoth production. The performance involved not only a coloured organ, an orchestra, dancers, chanting and incense, but a tower of light created at the foothills of the Himalayan mountains. For this reason, musicologist and translator of his notebooks, Michael Pushikin chooses to call it Mystery owing to the Greek origins as a ‘mystery play.’

“Mysterium was to be a sacred ritual, an apocalypse allowing people to astral travel to another dimension, and a ‘mission to regenerate mankind through art.’”

By that stage, Scriabin was heavily immersed in mystical symbolism, and was a pioneer of ‘The Silver Age’. This followed the golden-age— centred around Alexander Pushkin’s poetry—and the silver age added to this with modernism and symbolism. This meant a bit of tarot, astrology, religious philosophy, palm reading and often many other things in an attempt to find transcendent meaning.

Scriabin’s Mysterium was intended to help in this transcendence, although close to his death, a few people worried he'd lost his marbles. Even Vladimir Ashkenazy who has performed Scriabin’s music on many occasions. He mentions that Skryabin believed that his death would mean the end of the world, writing in his notebooks: ‘I am the apotheosis of world creation. I am the aim of aims, the end of ends.’

Pretty dramatic, hey? As someone who shares an interest in mysticism, musical teleportation and even a Christian name (albeit the female form), I have to say I am questioning my own sanity. Do I really believe such things as transcendence are possible? I’m still unsure, but if they were, I hope it would lead to unification, not destruction.

Claude Debussy (1862-1918) was another composer interested in symbolism; setting many of his works to the poetry of Marlemaine with an economy of notes to represent his words. He played around with rhythm and metre, and believed in the importance of silence.

John Cage (1912-1992) was a fan of quietness too. In fact he wrote a whole heap of essays about it. John Cage about silence. To John Cage, music as we define it, often sounds like people talking—telling us their stories, but in traffic; ‘sound is acting.’ In the above interview, he mentions artist and modernist Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) and that he sees art as a space-art, not time-art. He was interested in optical effects, like rotating disks and webs of twine, and often accompanied his exhibitions with a playful description like Rrose Sélavy (his feminine alter-ego) who ‘escaped from eskimos.’ John Cage refers to these as sonorous sculptures—not only did the discs move, they also produced sound—just like watching traffic.

‘People expect listening to be more than listening...when I talk about music, it finally comes to people's minds that I’m talking about sound...for I love sounds just as they are.’

Cage also quotes Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), the German Philosopher, as saying; there are ‘two things that don't have to mean anything...one is music and the other is laughter.’ Both will still give us deep pleasure and in Cage’s opinion; ‘The sound experience I prefer to all others is the sound of silence.’

Perhaps this is why he wrote his famous piece 4’33—of complete silence…

Or, is it? When we truly listen, does silence exist or do our surroundings become louder? Then again, it could be more like Bjork’s experience:

‘It’s all so quiet, (shh, shh) it’s oh so still (shh, shh), I’m all alone (shh, shh), and so peaceful until…’

BAA BAA BAA BAA! That’s the brass, by the way, and in my experience, they do tend to be slightly noisier than us string folk and always up for a party.It's Oh So Quiet - Björk.

If you’re familiar with Bjork, you’ll know her as another experimental pop artist. She had loads of fun costumes, great songs and if you have seen Dancer in the Dark, you will remember; a.) how sad it is, and b.) the factory scene using the machines as music—2000 Dancer in the Dark Scene Factory.

Bjork often used technology, science and space as inspiration in her music. In an interview with Electronic Beats in 2011, on her interactive music-creation software for children, she discusses the Biophilia album that accompanied it.

“What are the different elements featured on the album?

Let’s see if I can name them all… There’s gravity, tectonic plates, the human relationship to nature, viruses…

Crystals…

Yes—crystals, DNA, dark matter, cosmogony, lightning, and lunar cycles. Creation myths play a key role, too…”

That’s a lot of stuff, and includes quite a bit about what we’ve been talking about, and although some of these ideas may also seem a bit wacky, or just a little bit out there; they interested me. You see, I do believe—like them—that music is everywhere. We can’t always hear all of it, nor can we see it, but does that unequivocally mean it isn’t there?

43. “I am the apotheosis…” Vladimir Ashkenazy’s forward to Pushkin, M. (2018). The Notebooks of Alexander Skryabin.

44. Ibid.

#violettaandthevenetianviolin #musicalmusings #alexanderscriabin #johncage #bjork #scriabinandspace #authormusicians

Comments