The acoustic properties of timber

- Alexandra Louise Harris

- Dec 21, 2021

- 10 min read

Updated: Aug 8, 2024

Excerpts from Mighty Muso - Musings behind Violetta's adventures for adult minds and readers.

Antonio Stradivari (1644-1737), Nicolò Amati (1645-1684), and Joseph (Giuseppe Giovanni Battista) Guarneri (1666-1740) are all names we’ve probably heard of. Well, in Joseph’s case, his name was so long, he preferred to go by Del Jesu. I don’t blame him. Still, we associate each of them with exorbitantly expensive stringed instruments, made with the precious timber from the sacred valley of Cremorna.

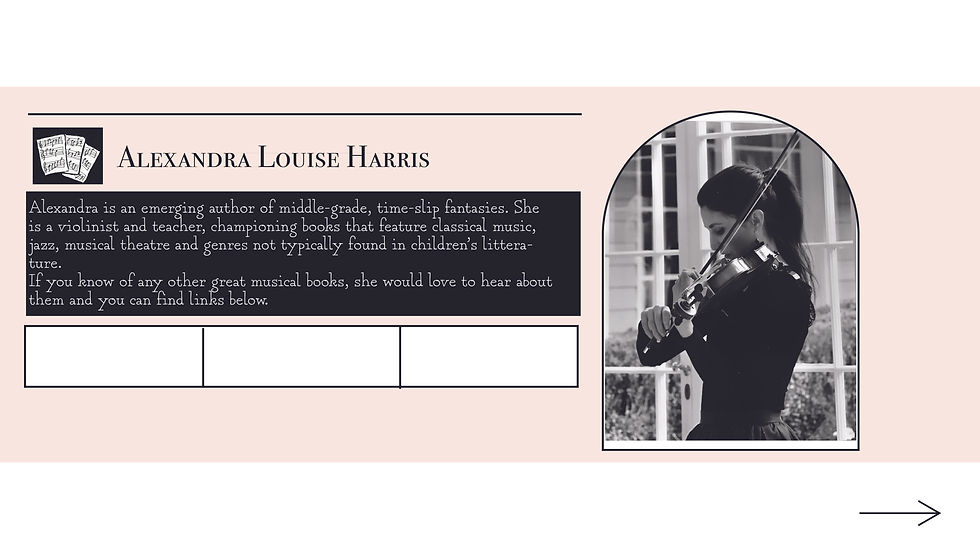

Sound like Lord of the Rings? Perhaps; but even if they aren’t made from secret magical wood, or arsenic containing varnish—more on that shortly—there is something unique about many violins. Take my violin—Ferdinand Maggini—for example (pictured left).

This was captured on the occasion he thought he might get replaced. That’s why he is frowning. I promised him it would never happen in a million years, and that even though there are many other lovely violins; he would always be my numero uno.

You see, I’ve known Ferdinand since I was twelve. He has helped me a lot. If you recall, I was very shy, and even then, I wasn’t really talking to many people. Therefore, Ferdinand became my voice. He shouted, he whispered, told stories, even jokes and most of all, while I was with him, I wasn’t nervous. I could stand up in front of a crowd and play whilst barely blinking an eyelid. (I am perhaps using that expression in the wrong context, as I’d end up with very dry eyes; but you get my meaning).

Anyway, Ferdinand is not very valuable in monetary terms. He’d probably only fetch a couple of thousand dollars; but he is very special to me. He is an 1890s German copy of the Italian Maggini violin, with an ivory nut, double purfling and a double scroll; and even though he doesn’t like cold weather, he continues to produce a sound that makes me happy. Of course, I have to work very hard; making sure I’m not squashing him by pressing too hard, using the right amount of bow, the correct contact point, watching my bow direction. Oh and then, I also have to play in tune, without too much tension in my neck, and my vibrato needs to be…

Huh? Oh yes, you are right. That is all very boring, so let’s forget all the human intervention that goes into playing—good and bad—and focus on the instruments themselves.

The origins of the violin are difficult to define. We know they were plucked long before they were bowed, and early versions were found in many places around the globe; including Egypt, Iran, and Ireland. However, most famously, violins are known to have sprung from Italy—from spruce and fir trees that legend has it; luthiers sought out during thunder-storms.

The greater the sound of the falling timber, the better the violin.

Another popular thought was that the first violins were created for beer and dancing. You know—jigs and pints, hornpipes and ailes, galliards and pané. Although when Nicolò Amati’s grandfather made his first violin in 1546, he may have had other things in mind; particularly the renaissance string ensemble, full of gambas playing the bass line, but no sopranos.

Hang on, what’s a gamba? I hear you ask. Well, that’s a good question. They are a little like a cello, played from the ground, or on a knee, rather than a shoulder. The bridge is also flatter, there are more strings and… how about I just show you a picture?

Nice, huh? Although, you can see, they might not be the most practical choice for doing a jig. (Incidentally along with small violins for ‘ladies’, Amati made a pochette especially for dance teachers).

Which brings me to that other popular question: ‘What’s the difference between a violin and a fiddle?’ Well, people might tell you: ‘You don’t spill beer on a violin,’ or ‘at least a fiddle’s fun to listen to.’ The truth is, there is no difference. A fiddle can play a concerto, just as well as a violin can play a jig.

(Image courtesy of the metmuseum.)

So what’s all the fuss about? Why are some violins worth ten dollars in a garage sale, and others worth gazillions? What makes the acoustic properties of timber so good? Is it the type of wood? Perhaps; and apparently, it needs to be old and dry. So dry that some luthiers dry theirs for up to eighty years, and others just chop up old tables.

No, really. They did.

The type of wood matters too. Spruce, and especially fir trees with a high resin content, make a higher velocity of sound. Maple is good too, although the front and back need to be different, as heavier timbers pick up the lower partials, whilst lighter timbers tend towards the upper. But does that mean all violins made of the same timber sound the same?

Unfortunately not.

So, is it the proportions? These matter a great deal, although the proportions used varied considerably. Stradivari violins are slightly smaller than the Guerneri, and my violins’ distant cousins—related only by name, not birth—are bigger again. Giovanni Paoli Maggini (1580-1630) made between fifty and seventy violins a tiny number compared to the six or seven hundred known Stradivari violins. However, Maggini’s were known for being ‘large and tremendously flat.’ Many other luthier’s modelled their violins on his, and Ferdinand is one of these copies. Replicas of the other famous makers' instruments were created too, made of fine timber; therefore they should all sound just as good...

It must be the secret varnish, then. I hinted at the arsenic ingredient earlier—suspected to have caused the premature demise of some luthiers, found hiding within the yellow pigment. This was occasionally saffron (we know that’s okay), however the others—made from crushed bugs, mango-eating cows, lead, or ‘orpiment’ (otherwise known as arsenic sulfide)—were slightly more problematic. The mysterious liquid was also said to comprise ‘etheric oils (essence) with soft resins,’ known as the ‘spirit varnish’ and to my mystical mind, we seem to be getting somewhere. (If it’s anything like the ‘spirit note’ in Fire Saga—the Eurovision movie—it will make me cry; even when I’ve watched it three times).

So, the secret varnish is a possibility, but there is still one other phenomenon—air. The string first vibrates against the air when it is played. More air is involved in the vibration through the ribs on the violin, between the outer front and back and around the sound post. Then that air comes out through the ‘f’ holes—the fancy parts on the top that allow it to vibrate.

More on that later, but the thing is; violins sound best when they are played. Okay, I know. Obviously. They wouldn’t make any sound otherwise, but what I mean is; they are claimed to lose their sound unless they are played. More than that, it is believed they can be trained and retain what they learn.

Do do do do, do do do do…(That’s the theme song of The Twilight Zone, in case you were wondering).

Anyway, a French man by the name of J.B. Drovel de Maupertuis, in 1724, looked into this. He wrote:

‘According to our observations, a vibrating string much more easily sets into motion those wood fibres that are in tune with it than other fibres.’

After that announcement, adjustments were made all over the place for centuries, but the strange inexplicable fact remains: somehow, the fibres in the wood respond to sound. Have you ever seen someone putting head-phones on a violin? Or keeping it close to a radio for a few hours every night? It sounds a little crazy, but these are things rumoured to help ‘play in’ a violin.

So, here come the scientists, and the article that particularly interested me was an Australian study conducted by commissioning two violins called…‘The powerhouse twins.’

See, intriguing, hey? Were they superhero violin-playing siblings? Hmm...not a bad idea, but no, they were violins made by luthier Harry Vatiliotis. He was a pupil of one of the first famous Australian violin makers—Arthur Edward Smith—and Ferdinand and I visited him several times. (You can watch a short documentary made about him here: Harry Vatiliotis: The violin maker aiming for 800 hundred violins before he retires).

One particular day stands out in my memory. We travelled by bus in the pouring rain, only to become horribly drenched and lost on our way there. Mr Vatiliotis kept Ferdinand over-night, as one of his cracks opened up (I’m afraid he’d been dropped in the early days), and the very kind Mrs Vatiliotis lent me her umbrella for the journey home. I remember it distinctly. It was one of those red, folding varieties and it helped tremendously.

Unfortunately, I chose to stand in the path of a giant puddle and a bus.

Anyway, when I returned Mrs Vatliotis’ umbrella and collected Ferdinand the following day, Mr Vatiliotis asked me to play something. He didn’t mind what, he just wanted to hear what my violin sounded like; and I remember his eyebrows raising. (Whether that was good or bad, I’m uncertain).

Mr Vatiliotis’ ‘Powerhouse Twins’ were made of European Spruce tops and maple bottoms—seasoned for over eighty years. One violin was played, and the other was unplayed. Both were measured, along with a factory-made control violin, before and after assembly; one year and then three years later. The process of measuring a violins vibrations is quite complicated, but one common way is via Chladni patterns (they are so fascinating, you really must check out this video Chladni Plates), with a shaker and magnet; or with a microphone, a hammer, and a pendulum. (Don’t ask me any more than that, I’m afraid I don’t know).

The results, however, revealed that to the trained listener and players’ ears, there was no significant change; despite several mechanical differences found in velocity. Another study suggested that intermediate or high-humidity contributed to the improvement one finds with playing, and others believe it has to do with the timber drying and an overall thinning of the varnish that aids the sound.

This is where I think this all becomes fascinating. The player of the Powerhouse Twin that wasn’t locked away all on their own, was a professional musician. Perhaps they had their own Ferdinand waiting to be played at home? How many hours did they spend playing? Was it the same violinist for the whole three years, or did it get passed around?

More importantly, did they get along? I know that sounds weird, but bear with me.

I discovered it was the same player; Romano Crivici, so I asked him. We had a lovely chat, and I learned he and his wife Karla are working on a documentary about Harry Vatiliotis tentatively titled: ‘The Last Violin’.

Romano and Harry have been close friends for a long time. Over the years, Romano has owned thirteen Vatiliotis violins and the last—Harry’s eight hundredth—is being made for him. The film is also created around the metaphor: ‘building a violin is like building a life.’ There are bones, necks, bodies and after sixty-seven years in the violin-building business, Harry can do it with his eyes closed; in the dark, just by feel. Until recently, his wife Maria would also sand the fronts and backs, knowing just from the sound how good the violin would be.

I learned so much from our conversation. In fact, it was an eye opener to a long held belief of mine. You see, like many, I’ve fallen into the mystical world, imagining an old violin like a ‘holy relic’ as Romano described it, and hearing a ‘silvery essence of the soul’. I have always thought that great players make their mark on violins. That they had a ‘magical sound that is transcendent’, and that the greats like Fritz Kreisler, Isaac Stern and Henri Viuetemps, all ‘imprinted’ their playing on their Del Jesu Guarneri violins. Likewise, I thought it essential that those residing in museums like the Smithsonian were regularly played in order to preserve their sound.

However, as Romano revealed, there are entire forests claiming to belong to the wood of the cross of Christ—well, not the trees themselves. I’m sure they know very well where they’ve been—and he raised the question. Are people trading in mystique?

In fact, that was the impetus behind the Powerhouse experiment, and for this reason, great care was taken to keep the tests blind. The chin-rests were painted, even kept warm, so that the university students who participated in the study were none the wiser. The Powerhouse violin became Romano’s, and he played it during the three years. When the colour began to change slightly during that time; the students were subsequently blindfolded.

Now, to my burning question. Did Romano enjoy playing the powerhouse violin? Well, he did. The Powerhouse twins were 'imbued' with the deep, viola-like sound (which Ferdinand has) and that Romano also enjoys. When preparing to take it on tour to Europe, however, he decided he needed something with more 'cutting' or 'projective power' and commissioned another violin from Harry Vatiliotis.

Interestingly, he noted the video footage taken at the time, sounded very different to his impression whilst playing. Under the ear, he found it 'very bright and harder to play' however, to his partner Carla (ex-principal flautist of the Australian Opera and Ballet Orchestra) it sounded perfect.

I sympathised with this predicament. In the photo of Ferdinand and I earlier, I had the same problem, as I prefer Ferdinand’s sound to my ear, whereas the violin on my right was apparently much louder from afar.

So how do we explain this phenomenon?

Perhaps in a number of ways. Romano believes: 'it takes a while to get used to a new instrument, for one's almost instinctive reflexes, physical responses to adjust [to] hearing ones own 'voice' with a different accent, or tonal quality.' I agree and this debate of how much we invest in a violin, psychologically, is a huge one. Can we ever be unbiased? After all, I myself have substantially varying moods in terms of how I perceive my playing, regardless of the instrument. In blind tests, newer violins have been known to triumph over the old, and when interior labels have been switched, opinion has been easily swayed.

Additionally, there is a valid point made. Itzhak Perlman would sound like Itzhak Perlman on any violin.

When the luthier, Leonhardt, stated: ‘Whoever understands the woods language has discovered the secret to violin making,’ I think he was onto something. You see, I believe, violins are alive. They have a voice of their own, participating in a conversation that we as the player have to learn to understand—despite the jury still being out on whether that soul exists from the beginning.

So maybe, just maybe, the following is close to the truth:

The wealth that’s there inside the timber,

lies there in the wood, but also the thinker.

Quotes:

“etheric oils…” Mailand, E. (1859) Découverte des anciens vernis italiens employés pour les instruments à cordes et à arceht, Paris. From Kolneder, The Amadeus Book of the Violin, p154.

“according to our observations…” Drovel de Maupertuis, J.B. (1724) Mémoires de l’Académie royale des sciences: “Mémoire sur la forme des instruments de la musique". Cited in Kolneder, ibid., p180.

“whoever understands…” Leonhardt, K. (1969). Geigenbau und Klangfarbe. Frankfurt. Cited in Kolneder ibid., p.192.

Comments