Why Did Handel Waggle His Wig?

- Alexandra Louise Harris

- May 13, 2022

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 3, 2024

That is an excellent question, and I'm so glad you asked.

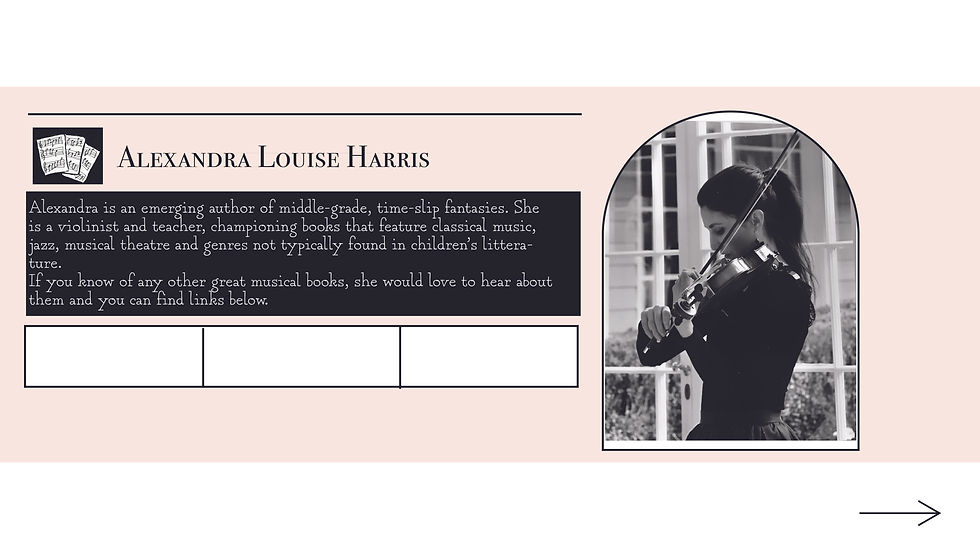

It was also the reason behind my marvellous idea to start a blog based around fantastic musical books I read. Exciting huh? I thought so, therefore, the first had to be Steven Isserlis' Why Handel Waggled his Wig—and more stories about the lives of great composers (Faber and Faber). It is in fact the second in what I hope is a series of middle-grade, non-fiction books, full of witty history. Just before we get into how fabulous it is, here is the cover:

Great isn't it? I mean, what a distinctive picture of Handel?

I also should mention my reason for delving into the book blog arena, is that I feel there are far too few musical books for children older than ten. Especially books featuring classical music. When I began writing Violetta and the Venetian Violin, I scoured the internet for resources. Whilst I found quite a few picture books and board books, middle-grade books were much harder to find. So sad! Therefore, when I do manage to unearth one, I wish to celebrate it in as many ways as I can.

Now, this book is soooo great. It is also for anyone—like most middle-grade reads—and I certainly learnt a thing or two. Perhaps, even as many as ten thousand! Oh, and before you read on, there may be some spoilers, but hopefully not too many.

So, onto the book itself. As the subtitle suggests, this is not just about Handel, or wig waggling, but about many other composers. Of course, there are sections dedicated to George Frederic Handel, but also Franz Joseph Haydn, Franz Peter Schubert, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Antonín Dvořák and Gabriel Fauré. Not only that, within each chapter, we learn about other famous composers and their relationship to these great people.

All humorously presented, it makes for an entertaining account. For instance, a hypothetical conversation with Handel's father—the barber... and surgeon. 'Hello barber - could I please have a short back and sides please? Oh - and while you're about it, could you take out my appendix? Thanks.' There is some twisting of bottom jokes where Handel was said by biographer Mainwairing to have "embarked on a new bottom." Then there are the real accounts of Handel's outbursts; "'Madam!" he shouted, "I know that you are a true she-devil; but I'll have you know that I am Beezlebub, Chief of the Devils."'

Crikey, says I... and that's not all. Steven—I hope he doesn't mind me referring to him by Christian name—surmised that 'Basically Handel had the constitution of an ox who does press-ups on a regular basis.' Hence the flattering portrayal of his stomach.

Then, it is onto Haydn, who I have to say I became rather fond of, despite his 'naughtiness' with women. Like many composers—and musicians even today—he struggled with poverty, but was content. 'Haydn would occasionally tell people that he'd been happier during these years of struggle than he was afterwards, when he was famous.' I learnt a lot about costumes, his life at Estehazy—there was even a chair that played the flute—and discovered he had a fondness for dogs. There are touching accounts of the months leading up to his death and his tutelage of Beethoven and Mozart.

The chapter on Franz Shubert (pronounced 'shoobert' as we are informed) is one of my favourites. Steven is obviously a great fan—as he is of all the great composers—but Schubert's music he describes as being heavenly, saying; 'he's the one who most often opens a door and shows you paradise.... In Schubert's music you hear the very first notes, and you know that you are there already.' Beautiful huh? He also had rather a cute nickname: "Schwammerl" —translated to mean "tubby", "mushroom", or "sponge"— and in the interests of humour, becomes known as a sponge-mushroom. Great name. We learn of his parties (Schubertiads), his shyness, his poverty, his fondness for Hungarian wine, and his affliction with syphilis. Then, there is this:

'The fact is that he was dead at the age of thirty-one—this love-able, tubby, awkward genius who loved life, loved his family and friends and loved music. And it's not fair. But he achieved more in his thirty-one years than most people would have achieved in ninety—no, nine hundred—years; and he left it all for us. Thank you, Mr Mushroom.'

I found that quite moving, and in fact, all the composers seem so real, it was like witnessing their whole lives passing in fifty pages. The 'painfully shy' Tchaikovsky, lisping due to a couple of lost teeth, crying at the sight of a sunset and with a neurosis I can relate to. You know, the one where you worry about everything, feel socially anxious and guilty if you win at cards. Not that I play cards, but like me, Tchaikovsky felt 'he didn't deserve to (win), and would feel sorry for his opponents.' Although we also share an affinity for walking, I unfortunately don't have his musical superpowers.

Next we meet the 'deeply religious' Antonín Dvořák and his pigeons. He enjoyed a good joke, and a game of skittles or darda (cards again). He was open, yet shy, and 'a musical genius with the heart and mind of a child, and the face of a dog'—in the most affectionate way. We travel with him and half his family to America, where he meets Indians selling 'magic medicines,' and composes his famous 'New World Symphony' and the 'American' quartet and quintet.

Finally, there is Gabriel Fauré, who's music is 'some of the most angelically beautiful, pure, touching, and ecstatic music that has ever been written.' I quite enjoyed meeting the dreamy Faure—dreamy in nature and appearance. It seems he was quite the dish. Like the other composers, he struggled financially and supported his family by teaching; however he comfortably mixed with Parisian high society and was generally liked by all. He was a little vague, disorganised, and often misplaced things, but in his music, Fauré hoped 'to lift us "as far as possible above what is."

Poverty, death, gambling, suicide, madness, affairs, homosexuality, syphillis, cholera—refreshingly, none of these details are spared from the reader. Yet, they are sensitively treated and sprinkled with humour when things get too dark. If that wasn't enough, for classical music lovers, Isserlis' insights into the works of these great men—and his suggested listenings—are incredible. I've always had a dreadful memory for opus numbers and such-like, so it is a resource I will certainly be returning to. In fact, I've highlighted most of the book.

Well, as you can see, I loved it and I really hope you do too! If you manage to find some golden nuggets of musical literature, please let me know. You can also share your thoughts by commenting on this post or by emailing my through my website. Happy reading, listening and music-making!

#classicalmusicbooksforchildren #childrensbooksaboutcomposers #whyhandelwaggledhiswig #stevenisserlis #violettabookseries #creatingstoriesthroughmusic #middlegradebooks #musicalbooksformiddlegrade #booksforyoungmusicians #middlegradereads #violettaandthevenetianviolin

Comentários